The breakage and amelioration of Stereo(TYPE)s with Dr. Jonah Mixon-Webster

"Stereo(TYPE) is coming from this deep ambivalence that comes up when you have to take the good with the bad and integrating some of the experiences that I wish never happened to me with the actual true beauty of being Black."

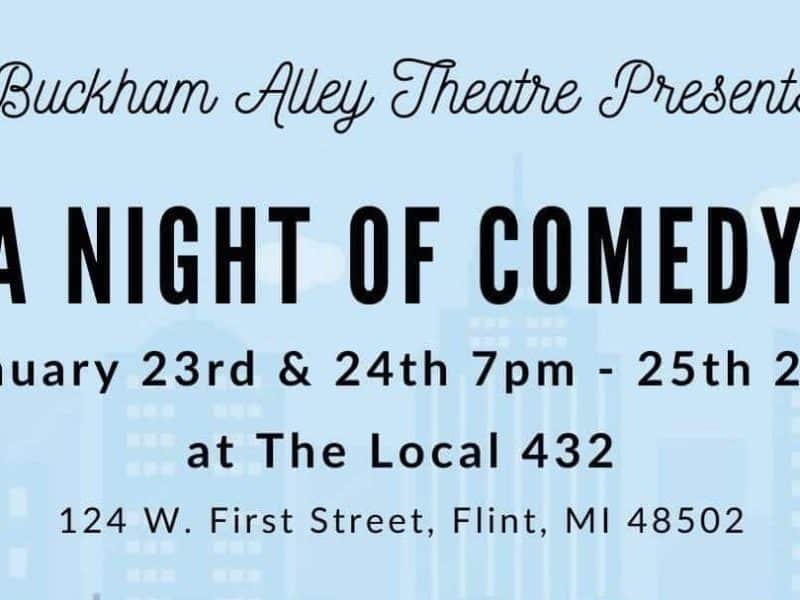

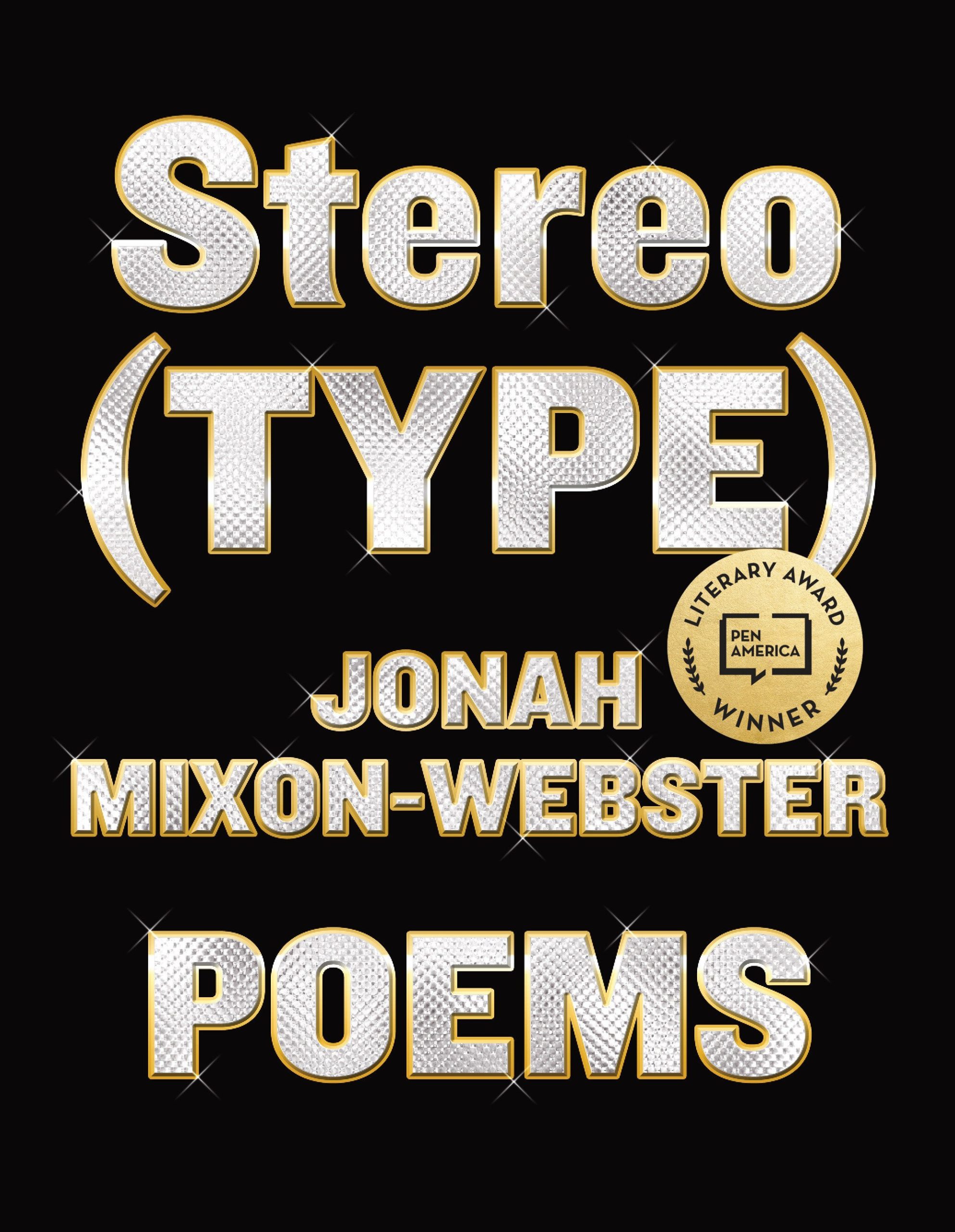

FLINT, Michigan — There are many unusual people in Flint, but none quite like the enigmatic Dr. Jonah Mixon-Webster. Whether through his personal life as a Black queer man, professionally as a Ph.D.-holding university professor, creatively as a poet and conceptual/sound artist, or with other nerdisms, Mixon-Webster is the definition of an oxymoron. He is every bit of unorthodox, intriguing, and unpredictable—like his PEN America/Joyce Osterweil Award-winning collection of poetry, Stereo(TYPE), which he calls a “multimedia immersive experience, performance, and critical theory of Blackness.”

Yet, Stereo(TYPE) is but a glimpse into the internal strife of Mixon-Webster, born and raised in Flint, and molded by the lack of personal “representation of what a Black man [or] a gay man” was, and “resisting [the] normative performances” of both.

Scattered across its pages are his diverse encounters, packed with blunt authenticity that only the creative arts can shoulder. “It’s still a process even just talking about it because those same internal voices and systems of policing myself are there,” Mixon-Webster says, and as such, there’s something beautifully tragic about his work. His words grip you, tugging at the end of your shirt like a child, begging you to pay attention. They’re reminiscent of a lover’s arms wrapped around you until they become a bitter memory. Still, they speak to your soul, eliciting an emotional response and a connective resonance of generational moments. It is the power of Mixon-Webster and the world created through the written and studio recordings of his poetry.

“Stereo(TYPE) is coming from this deep ambivalence that comes up when you have to take the good with the bad and integrating some of the experiences that I wish never happened to me with the actual true beauty of being Black,” he says, lighting a cigarette. “I’m always living in that space of being stupefied by being alive. So because of that, in the work that I produce, I want it to reflect and perhaps create its own stupefaction.”

And with it, Mixon-Webster is profoundly himself appearing before me with uncombed hair, a box of Newports, dressed in all black, covered in tattoos, wearing a gold Rolex on the one hand and a black braided bracelet on the other. At first glance, he is intimidating, a visual representation of the powerful yet angry Black man who “grew up in this cultural environment,” moving between a scowl and a smile on his face. His energy is loud and present, which protects and gives space to incredible intuition and a sensitive spirit cultivated in forced isolation. Yet the language—both written and verbal—Mixon-Webster commands to describe his oxymoronic life comes as a reproduction of Black American culture, the constraints it can have, and the innate freedom it possesses.

“I used the N-word in the book so much. That word itself, number one, is a conjuring word—a magic word. But, also, it’s a word we’ve seen some ugly s*** come out of it,” he says with a laugh. “But ambivalently, paradoxically, we’ve seen some beautiful s*** come out of or made with that word and its power in that. Black folks teach the rest of the world how language works.”

Reminiscent of that word, our conversation and the nature of it hold a magical realism. It is, to take from an excerpt to describe Stereo(TYPE), “at the intersections of space and self, race and region, sexuality and class.” We aren’t downtown, in a studio, or a home. We are inside his truck, driving around his childhood neighborhood on Flint’s northside with old-school R&B classics from the 60s, 70s, and 80s erupting out of his speakers. In between our singing, we’re focused on how his poetry “critically and creatively approaches and contends with some of the very complex experiences of being Black that’s racialized, policed, and sexualized.”

We ride around looking at the Black American experience that engages with itself through children playing, families sitting on porches talking, laughing, doing hair or yard work, and staring at us as we stare at it. It is a first for the both of us, one that reeks of excitement, is reflective of his life and Stereo(TYPE), but creates an atmosphere of vulnerability and intimacy. Then, he takes me by a house in the neighborhood where he was publicly outed for being gay—one of many moments that found him simultaneously a part of yet separate from Black culture—and in these moments, Mixon-Webster’s inherent sensitivity is on display.

“I had to learn the relationship between vulnerability and courage very early. This [house] is where a group of kids came to tell my mama I was gay. I was nine years old. That’s where my reading and writing started because I was outcasted,” he says in a dreary voice. “I had to find ways to nurture and teach myself how to move through a world that hates you—even if it’s your own people. Through this experience, I understood how Black identities get formed in these very tight spaces.”

As we journey across Carpenter and Clio Road, Dupont Street, Flushing Road, and end at Rube’s Bar & Grill on Chevrolet, Mixon-Webster recalls early writings about murder mysteries, the love triangle between music and writing, and the spiritual nature of his successes. It comes on the heels of listening to the recorded audio of two of his poems: The Hang Around Blues and Tried Too Blues. As soulful voices caress our ears and bring to life Mixon-Webster’s poetry, he remarks how Stereo(TYPE) isn’t just a written experience; it’s a listening one too. One that encapsulates the totality of his experiences and speaks to a diaspora of people.

“I think right now one of the great disservices we see is Black poetry separated from Black music. The project tries to direct or guide attention and more continuity between Black artists of various modes and methods to produce that dynamic anti-monolithic experience,” he says. “I want Stereo(TYPE) to be a monument to that tradition of amelioration that Black folk have done.”

You can find out more about Jonah Mixon-Webster and his poetry on his website and follow him on Twitter and Instagram. Stereo(TYPE), published by Alfred A. Knopf, releases July 13. Pre-orders are open.