Partner Partner Content MARESA promotes healthy eating and fitness in the rural Upper Peninsula

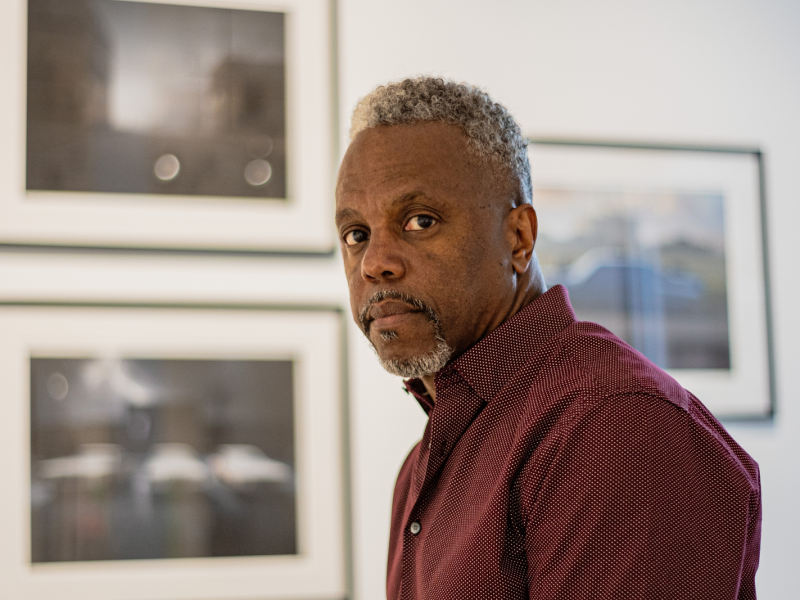

The Marquette-Alger Regional Educational Services Agency (MARESA) is working with 18 elementary schools in seven counties in the central UP to encourage healthy eating and physical activity.

This article is part of Stories of Change, a series of inspirational articles of the people who deliver evidence-based programs and strategies that empower communities to eat healthy and move more. It is made possible with funding from Michigan Fitness Foundation.

Editor’s note: Due to closures because of COVID-19, educators are moving SNAP-Ed programming to alternative learning platforms.

The remoteness of communities in Michigan’s central Upper Peninsula creates obstacles to healthy food choices and physical activity for many families. Some families live an hour away from the closest grocery store and often pay higher prices for limited, healthier options. Families often live far apart, making after-school playdates difficult. Many children don’t have bicycles.

“The area is very rural and some kids don’t have anybody around them to play with,” says Colleen Msuya, a fifth-grade teacher at Escanaba Upper Elementary School in Delta County. “Kids in town can get out and ride their bikes for a couple of hours and be active. Other kids just don’t have bikes.”

However, the Marquette-Alger Regional Educational Services Agency (MARESA) is working with 18 elementary schools in seven counties in the central UP to encourage healthy eating and physical activity. Six years ago, MARESA launched a Healthy Schools, Healthy Communities program, which uses curriculum provided by Michigan Fitness Foundation (MFF) to promote healthy eating and physical activity in the classroom.

The program is funded with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) grants from MFF. SNAP-Ed is an education program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that teaches people eligible for SNAP how to live healthier lives. As a State Implementing Agency for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, MFF offers competitive grant funding for local and regional organizations to conduct SNAP-Ed programming throughout Michigan.

The classroom lessons last 30 to 50 minutes and focus on nutrition, healthy eating, and physical activity. Each lesson includes a recipe demonstration and healthy food tasting.

“A lot of our kids don’t have experience with healthy foods,” Msuya said. “Half of my class said they’d never tasted a red bell pepper before. To me, that means parents haven’t either. They’re not likely to give their kids something they’ve never had.”

Some of the students’ favorite healthy snacks have included veggie wraps, a whole-wheat tortilla filled with hummus, shredded cheese, carrots, broccoli, snap peas, and other fresh vegetables. Smoothies and fruit roll-ups are also popular with students.

“That part of the lesson is the most important and where the learning happens,” says Rachel Bloch, health education consultant with MARESA. “Students are hands-on with the food. One of our goals is to help them learn recipes that they can take home and make in their own kitchens to share with their family.”

Bloch says the team is conscientious about spotlighting healthy foods that are available in community grocery stores. MARESA offices are in Marquette, the UP’s biggest city, but many of the schools are in communities where the nearest grocery store is an hour away.

Students also receive FitBits during nutrition education lessons, short physical activity breaks designed to get kids up and moving around.

Students are taught how important it is to be active and that sitting too long can make them feel sleepy or hinder their concentration. Staff emphasize the importance of 60 minutes of physical activity each day, which can be as easy as going for a walk.

“We try to embrace whatever community we’re in and what kind of resources are available,” Bloch says, noting that amenities vary by community.

Escanaba and Marquette, for example, have recreational facilities and programs. Many communities have access to hiking and recreation trails, which provide an outlet for physical activity either for free or at low cost.

“We’ve made a point to talk more often about exercise,” Bloch says. “It’s working. We see kids are moving around more. In the classroom, for example, we talk about how sitting too long can make them feel.”

Healthy Schools, Healthy Communities has had an impact. SNAP-Ed has been a catalyst for change for families. The program has served about 2,000 students since it launched.

“We’re seeing that kids are bringing healthier snacks to school,” Bloch said. “A lot of the schools have salad bars but kids weren’t eating from them. So we’ve talked about salad bars in the classroom and encouraged them to try different foods in the cafeteria. And now they are! We try to connect the lesson to the school and the community.”

The program also encourages teachers like Msuya to reiterate messages about healthy eating and physical education during other times in the classroom.

“It really enables us as teachers to talk about these things,” she said. “We’ll ask students questions like ‘What did you do last night? How did you get active? What did you eat?’ I think it’s had an impact. Now we hear kids talking about eating healthy and being active.”