A new pilot program identifies families at risk and pairs them with peer mentors and benefits navigators, getting the state more involved in addressing the root causes of child abuse.

This article is part of State of Health, a series about how Michigan communities are rising to address health challenges. It is made possible with funding from the Michigan Health Endowment Fund.

Michigan’s child welfare system depends heavily on teachers and school staff to report suspected child abuse or neglect, usually by calling the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) abuse and neglect hotline. But in March, COVID-19 closed the schools and those calls dropped by nearly 50%.

“We saw that decrease almost immediately, the day after the stay-at-home order was issued and schools closed down,” says JooYeun Chang, senior deputy director of the MDHHS Children’s Services Agency. “We have, in the last couple of months, seen that number go up a little bit, but not significantly.”

Chang says it’s hard to say if the drop in calls means abuse and neglect are continuing and not being reported. Of the 190,000 calls the agency receives per year, it refers 50-60% of them for additional work including an investigation.

“In some ways, the hotline itself is not a good predictor of community need or child endangerment,” Chang says. “However, it’s the system we have today.”

But in Wayne County, MDHHS and nonprofit Brilliant Detroit are working to rethink that system through a new pilot program. The program identifies families at risk and pairs them with peer mentors, who offer support; and benefits navigators, who connect families to community resources such as food, housing assistance, education, and employment. While other programs across the country include either peer mentors or benefits navigators, Chang believes this program is the first to enlist both as a means to prevent child abuse and neglect.

“The question was whether or not kids are experiencing bad treatment and not coming to our attention. We are not sure we know the answer to that,” Chang says. “What we did not want to do was wait until things went back to normal. We wanted to be proactive.”

Cindy Eggleton, co-founder and CEO of Brilliant Detroit, says approaching child abuse and neglect through a preventive strategy that addresses social determinants of health is a “game changer.”

“The families are fully supported, not just in terms of preventing child abuse, but really supported in how to lead a resilient and happy life,” she says. “It’s different than having a case manager. People feel totally connected and supported by someone who understands what they’re going through and holds them accountable.”

Parent partners: Support, not compliance

Five ZIP codes in Wayne County lead the state in the number of children removed from their homes and placed in foster care. The MDHHS/Brilliant Detroit pilot created a list of families to focus on by overlaying those zip codes with past reports on families at risk for abuse and neglect.

“We are trying to move our system further upstream. Instead of waiting until an abuse or neglect occurrence, then relying on a report, and then going out to investigate to see if something is so serious that we take action, we want to get ahead and help earlier,” Chang says. “This could be a first important step towards shifting our adversarial system to looking upstream to support people in their own communities.”

With a history of working side-by-side with its community, Brilliant Detroit had trained community members as peer mentors in its other programs. These mentors, “parent partners,” are the foundation of the pilot program. Parent partners, who offer lived experience and have children of their own, complete extensive training in mental health peer support and how to work within MDHHS systems.

“The group we have coming into this project could not be kinder and more empathetic,” Eggleton says. “They have a clear understanding of what it is like to be in a situation and not have support.”

MDHHS had already begun to formulate plans for shifting the paradigm of how Children’s Protective Services functioned before the pandemic, but COVID-19 accelerated those efforts.

“This is the first time in my career where we’re a part of the community, not that agency that interferes with families,” says Lynette Wright, deputy director of Wayne County Children’s Services at MDHHS. “Families are freer to discuss issues with a peer mentor than with a professional. We are going to impact them in a very deep way that professionals aren’t able to get to.”

Addressing root causes of domestic violence and substance abuse

According to Chang, two key underliers of child abuse and neglect are domestic violence and substance abuse. Parents who are victims of domestic violence hesitate to share their plight because they justifiably fear further reprisals from their abuser and having their children taken away. Similarly, parents experiencing substance abuse are not likely to share that information with a system that has the power to incarcerate them or remove their children.

“Those are two things that can be really scary to navigate from a systems level and really easy for folks to give up on, leaving them in a deep sense of social isolation,” Chang says. “We want our mentors to help these parents learn how to build social support networks.”

Through peer support and group events with other parents in the program, parents experiencing these issues find more opportunities to seek help and overcome obstacles.

“I hope that it will break the cycle of family violence, which is pivotal to the family separations that have been the markers of our agency. If we build the internal capacity of parents at the earliest stages, we can really allow that family unit to avoid actual incidence of abuse and neglect and allow that young person to experience a strong and healthy family,” Chang says. “We want to prevent kids from experiencing these horrendous incidents of abuse and neglect in the first place, so they don’t have to experience the additional trauma of family separation.”

While domestic violence and substance abuse occur in all demographics, poverty is a primary driver of both.

“Engaging with these families and just hearing from them in terms of what they need provides a different perspective,” says Annie Ray, child welfare director for MDHHS Children and Family Services in Western Wayne County. “Because we are working together with them to identify what they need — help with utility bills, job assistance — and look at the other issues like substance abuse, we have an opportunity to engage with our families more strongly.”

Eggleton says she “strongly believe[s]” in the model.

“We see it in the Brilliant Detroit programs every day: peer support makes a gigantic difference,” says Eggleton, whose mother grew up in foster care. “People want to do their best by their kids. They really do. I’ve seen firsthand, when people get the support that they need … it really works.”

“Systems can fail but people won’t fail each other”

In addition to meeting with parent partners one-on-one, families take part in group activities with topics including parenting, anger management, mental health supports, and how to get a GED or find tutors for children.

“Individuals get a ton of support from the parent partner as well as from each other. I think that’s the beauty of this,” Eggleton says. “Systems can fail each other but, given the right conditions, people won’t fail each other. This is about total support, not about compliance.”

While MDHHS has always offered preventive and education services to the highest-need families on the cusp of entering the foster care system, organizers hope that the wider preventive network will support resilience among low- and moderate-risk families.

“What we learn here in Detroit will be a really important test in how to do that,” Chang says.

She notes that for generations, the child welfare system has been rooted in a belief that some people are simply “bad parents” and the only remedy is to separate them from their children.

“This is rooted in racism, classism, and lots of other ‘isms,'” she says. “Hopefully, we will restore what has been taken away from so many generations of families in this country, not only keeping individual children safe but helping to support entire communities and bring our system back to what it should have been, as well.”

A freelance writer and editor, Estelle Slootmaker is happiest writing about social justice, wellness, and the arts. She is development news editor for Rapid Growth Media, communications manager for Our Kitchen Table, and chairs The Tree Amigos, City of Wyoming Tree Commission. Her finest accomplishment is her five amazing adult children. You can contact Estelle at Estelle.Slootmaker@gmail.com or www.constellations.biz.

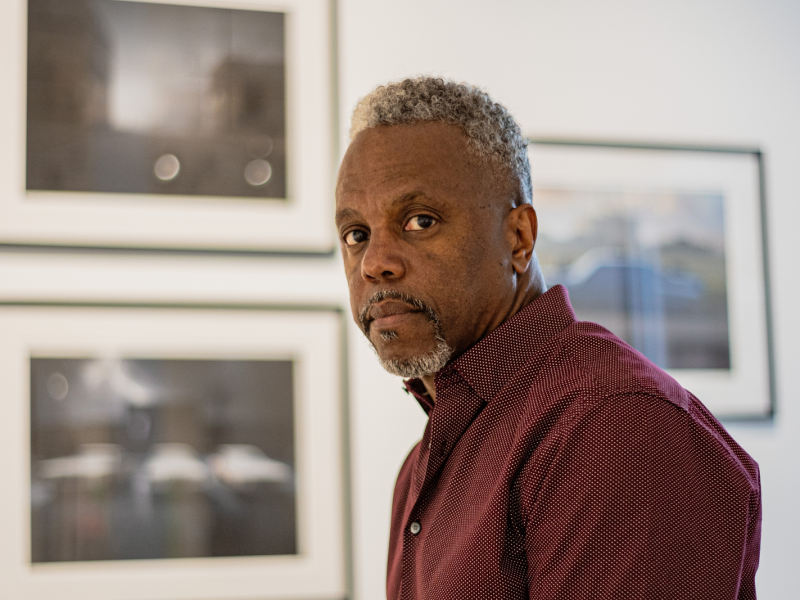

Brilliant Detroit photos by Nick Hagen. JooYeun Chang, Annie Ray, and Lynette Wright photos courtesy of MDHHS.