ASL advocate helps residents connect to Flint’s silent community

Linda Bell teaches a weekly ASL class instructing enthusiastic students like Janet Hughes alongside co-teachers like Brian Whittington when she’s not working on developments for her app, Bell Tech Communications set to showcase Feb. 13.

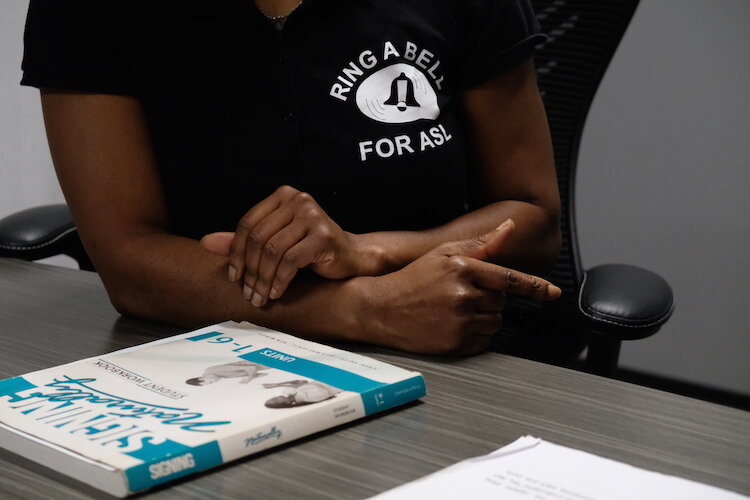

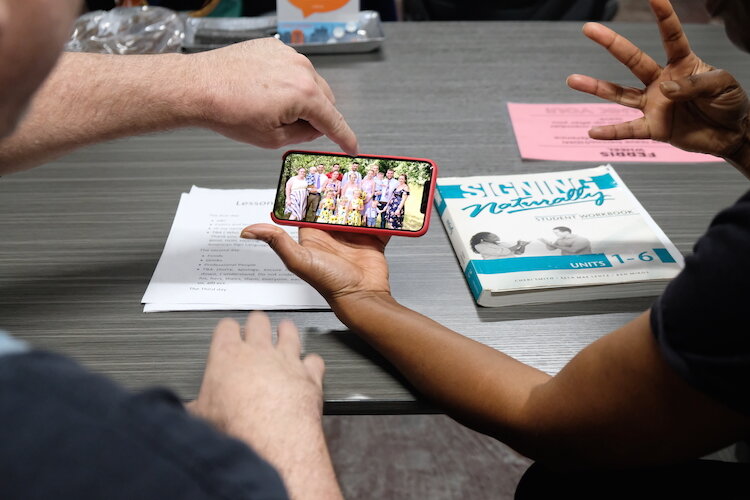

FLINT, Michigan—Janet Hughes, 59, works second shift for her retail job but devotes her free Monday evenings to learning sign language on the third floor of the Ferris Wheel building downtown with Linda Bell’s Ring A Bell ASL class.

“I’ve been working in retail all my life so I started seeing the deaf community come and shop at the stores that I work at and there was no one to help them,” said Hughes. “And I would feel bad because they would leave the store frustrated because no one could communicate with them or try to understand.”

From then on a spark had been lit, said Hughes, and she is determined to devote her education to learning how to reach the “forgotten community.”

Bell teaches a weekly ASL (American Sign Language) class instructing enthusiastic students like Hughes alongside co-teachers like Brian Whittington when she’s

not working on developments for her app, Bell Tech Communications set to showcase Feb. 13.

Flint’s lack of bilingual resources was most emphasized by Flint’s Water Crisis that left many vulnerable communities in the dark about water contamination. Bell would receive hundreds of phone calls from the deaf and hard of hearing asking for her to assist them in doctors and counseling appointments. With no state certification, Bell found herself unable to help but simultaneously wanting to be hundreds of places at once.

A 2018 5-year American Community Survey, found that approximately 3, 213 of Flint residents identified as having a hearing difficulty and though Michigan is among the 45 states to recognize ASL as an official language, its place in primary and secondary education has remained arbitrary. Just last year there were protest demonstrations over the MSDB’s decisions to hire school administrators who lacked the ability to sign ASL. The University of Michigan-Flint had excluded ASL from its foreign language requirement until its 2010 decision to allow transferred credits from Mott Community College.

In class, Hughes will hold an ASL conversation with co-teacher Brian Whittington, 53, a man who considers his ability to read lips both an advantage and a side effect of being denied resources for his deafness, including being able to sign in class.

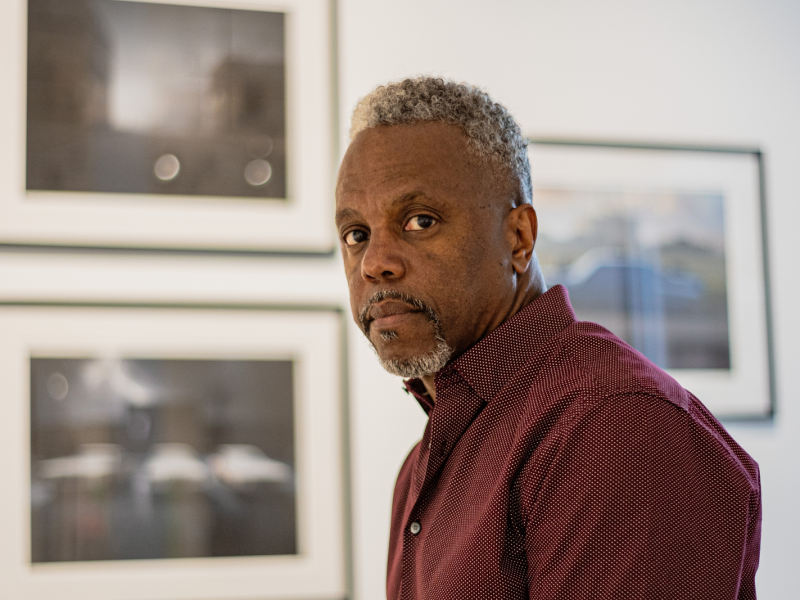

“When I was growing up they used to tell us to stop signing. They wanted us to speak,” said Whittington. “Only a lucky few found a deaf school [to go to] but everybody else went to mainstream [schools], meaning that the deaf and hearing were mixed together.”

Interpreters weren’t always a guarantee, said Whittington, and although he considered himself an intelligent child it was impossible to watch the teacher and interpreter, and take notes at the same time. He found himself constantly behind, until eighth grade when he’d finally had enough and enrolled in Michigan School for the Deaf and Blind (MSDB), where he graduated in 1985.

Despite being home to MSDB, Flint’s promotion of American Sign Language education has been hit or miss for as long as those like Whittington and instructor Bell, 55, could remember.

It’s one of the reasons Bell launched her education program, Ring A Bell for ASL in 2019. It’s the fourth-growing language learned in U.S. classrooms, said Bell, and it’s a language she has had to use her entire life.

“ASL has been my life,” said Bell. “ I don’t remember a day I don’t use ASL.”

Bell remembers in the ’80s that the national news circuit was abuzz with stories of deaf and hard of hearing individuals being shot by police, unable to hear, communicate, and comply. The expressive body language needed to communicate in ASL was often mistaken by police for aggressive behavior. News stories like the 1981 shooting of an unarmed deaf man named Glen Mattila in Belleville, Illinois were one of many stories that hit close to home and inspired her to become a staunch advocate for the deaf community, said Bell.

At the time, she was attending Flint Northern High School, as a single child and full-time translator for her deaf mother on East Piper Avenue.

“I was doing sign language for my mom going to the doctors with her, helping her with groceries,” said Bell. “Translating at the Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) so we could get our food stamps, so we can get utilities for the house.” From a young age, Bell stepped in to do the translating that government and public offices considered optional.

Bell graduated from Mott’s deaf studies, general education and ASL program in 2003 and would devote the next five years of her career translating for Mott Community College, Baker College, and UM-Flint, all while facilitating her own interpreting business.

“[I was] going to doctor’s offices, counseling offices, hospitals wherever I [was] needed,” said Bell. Though interpreters were in high demand, it was creating a problem, said Bell. Translation agencies were being undercut by freelancers and it was getting the state’s attention.

In 2013 the Michigan Department of Civil Rights’ Division on Deaf, Deafblind and Hard of Hearing enacted the 2007 Michigan Deaf Persons’ Interpreter Act. Working interpreters would need to undergo re-certification with the state by taking the Michigan Board for Evaluation of Interpreters Performance Test (MI-BEI). The test provided a level of standardization that according to Bell isn’t always honest about how the language is actually used.

“That’s why they’re struggling with less interpreters because people are like, ‘this is unrealistic,’ ” said Bell. “They’re putting words into a test that they know people don’t even use in [the deaf] community.”

In her opinion, the state enforcement of the test weeds out Children of Deaf Adults (CODAs), those like herself who were children of parents that may have lacked the basic skills of reading, writing, and access to a full education.

Bell took the test in 2016 with the encoded facial expression, body language, and ASL vocabulary she had used her entire life and failed. As a result, she can no longer be paid to interpret, but it hasn’t stopped her from finding other ways to bridge the worlds of hearing and the deaf.

“I came up with the idea for an app to help people be more inclusive,” said Bell. “It’s not an app for translation. It’s an app for communication.”

Her app takes out the middleman of an interpreter entirely—allowing hearing and non-hearing people an equal linguistic playing field through the power of their smartphones.

Due to years of work, Bell has qualified for 100K Ideas’ Pitch for $K and will present her app, Bell Tech Communications, Feb. 13 at Genesee Valley Mall.

“We need somebody who’s doing something and [Linda’s] doing it. I’m very happy,” said Whittington. “I’m part of a team too…there’s no gray area. No more uncomfortable feelings.”

For more information or to sign up for a 6-week ASL course call at (810)-513-1883.

Correction: The 100k Ideas’ Pitch competition was held Feb. 13 at Brennan Community Center