Remembering Sandra Brewer: A Kamikaze in Three Acts

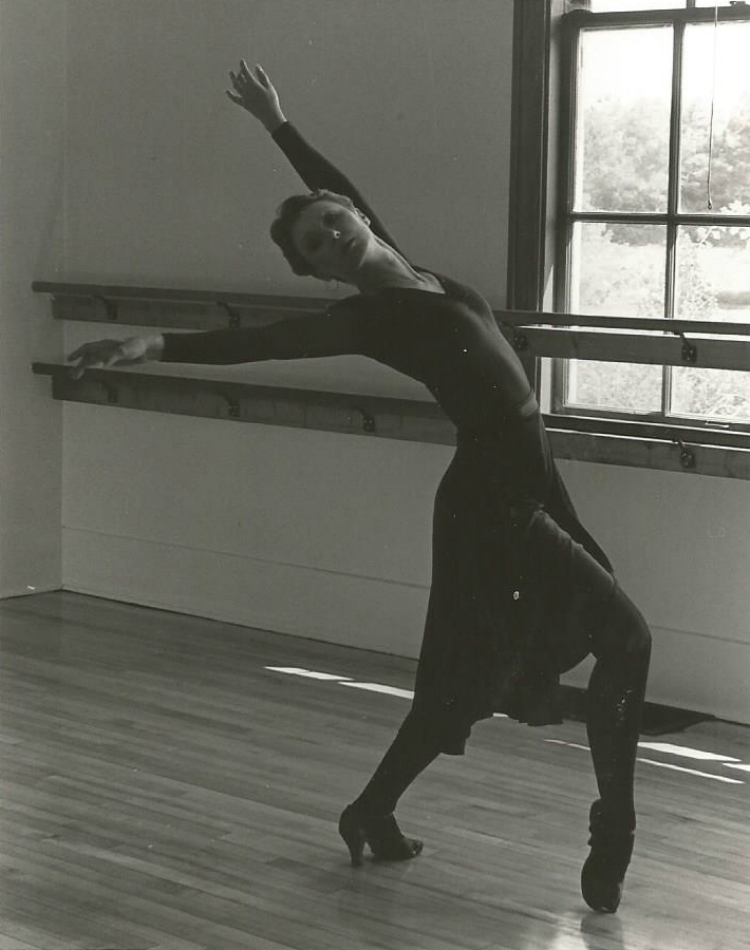

Broadway, potato festival—it didn’t matter. Famed local choreographer and dancer Sandra Brewer taught that people deserved to be entertained, and entertainers deserved a chance to give their best performance. Always.

Act I

You are not allowed to see Sandra Brewer cry.

You have not earned it, because—despite how much she would give you, help you, talk with you, no matter who you were—that level of friendship is as hard to earn as it is worth it. You don’t get to see Sandra Brewer cry because she is too tough, tougher than you, tougher than the people you know, and has worked harder, too. In fact, if you were lucky enough to be the kind of person in front of whom Sandy might cry, then you would, as Sue Mackenzie had, even then only have seen it twice in your life.

Sandy died May 30, at 72, after a battle with cancer—a battle she won, for the record, because no one, nothing, not even cancer, has told Sandy what she could or could not do. She did not recover from surgery, but she did come home with the intentions to see family and rest, and at that, too, she succeeded.

And, so, when you meet Sandy for the first time, sometime around 1981, and she is talking with Mackenzie, you do not get to see her cry. But you should know that she was in the original plays like “Cabaret” and “Chicago,” working alongside Bob Fosse and Gower Champion, that she briefly moved to Los Angeles to be on television and succeeded at that as well, and that she had toured the country in some of the most well-known shows that have ever been performed.

When you meet Sandy, you should also know that she briefly considered and dismissed a career in the medical field, and that she then resumed teaching dance with a partner, a venture which at this point in our story has fallen through.

But you do not get to see her cry now—so do not watch—but listen for a moment as Sandy Brewer asks, perhaps for the first time, what might be the most un-Sandy-Brewer-like question she would ever ask: “What am I going to do?”

What was Sandra Brewer going to do?

Well.

Act II

It was a question she thought she’d answered at 18: Sandra Brewer was going to dance on Broadway.

But to do that, she needed money, and therefore a job, and so she did it in the way that would become her style: Kamikaze. Attack with everything. She opened her own studio. She was 14 years old.

“We had a basement at the house and my dad, he fixed up one whole area with paneling, and there was another area with a door and he put up mirrors and a bar, and turned it into a studio,” said her brother, Don Brewer,.

“The whole idea was so that she could save up money and go to New York and work on Broadway.”

At 18, having just graduated high school as salutatorian (“She could attend class, open up a book and read the chapter one time, and ace the test. There was nothing to it,” her brother said) she packed her things with a friend and their dance teacher drove them from their Swartz Creek home to New York City, dropping them off at the YWCA.

She was there—New York City. Home to Broadway. Her heroes. Her dreams.

In her first letter home to family, dated July 7, 1963, after one night and one day in New York, she described the city to them. She called it “exciting, and surprisingly, friendly,” but the first three words she used were “big, dirty, (and) noisy. … I think I washed my hands every hour or so today and they’re still filthy.”

But there was also Broadway, only a block away from where she was staying.

“There are theaters side by side all the way. It’s really exciting,” she wrote.

She and her friend walked the city and took subways (“if you think riding a roller coaster jerks you around, you ought to try a subway. When it first started up, I almost died”) looking for better places to live. They also found the American Ballet Center in the heart of Greenwich Village, a place she said made her “so scared we turned around and walked right back out, shaking all the way.” The next day, she planned to return and enroll.

“P.S.,” she wrote. “I’m not lonesome yet.”

And so Sandy began to do the thing that so many people have left home to do, to live a dream, and she discovered all the very non-dreamy struggles that come with it. There was the housing, to start. After the YWCA, she found a place to stay in a home for girls, that had so little space she asked her parents not to send her winter clothes until winter, when she hoped to swap them out because she had nowhere to put them.

There was food. In the second place she found to live the coffee served to them by their “feeble” landlord was “that awful instant stuff and so strong that I was sick to my stomach the rest of the day.” Once she started dancing every day, she felt like she never had enough to eat. She weighed 117 pounds.

And there was New York itself—the noise, the crowds, the dirtiness of it all.

“It seems there’s no escape from the heat and the crowds around here,” she said, after a failed trip to the beach when she and her friend couldn’t fight their way to even see the water.

The best thing she had to say about New York, aside from Broadway and dance, was when she got out of Manhattan and to Brooklyn to go to a museum, but what she liked best was, “it was on a river and the scenery was real pretty. It actually had trees and water almost Michigan and not just pavement and buildings and dirt all over the place.

And there was dance.

Her parents wrote to her, supposing that the dancing was vigorous.

“Vigorous isn’t the right word,” she wrote back. “I usually die, yes die, in point classes,” she wrote home.

“Mr. Griffiths, the teacher we have for technique three days a week, actually takes pleasure in seeing us suffer. … I had one of his classes this morning and I still have the battle scars.” Her feet hurt, she was sore, and constantly exhausted.

But, she said, “His classes are really doing me good.”

After weeks in dance she and a friend auditioned to dance in a nightclub. The other girls could not dance, but they were “dolled up” with makeup and fake eyelashes, and she didn’t get the gig. They did.

Throughout her letters home is a note of optimism, an understanding that this was what she signed up for. It’s what you did if you wanted to live the dream, knowing that plenty of people don’t make it.

Three months later, she made it.

The first show she booked was “Camelot,” and she left on a national tour.

“She worked non-stop from there. She never stopped working,” said her son, Don Brewer. “She never did the struggling actor thing. She was instantly successful.”

She went on to have a 16-year career on Broadway, performing and choreographing for some of the most famous shows to date, including “Cabaret,” “Chicago,” “Pippin,” “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” and “Sugar.” She worked with renowned choreographers like Bob Fosse and Gower Champion, for whom she was his “main dance captain.”

It was during this time she met her husband, Gerry Verheeck, while they were dancing together in “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying,” and in 1975, after spending most of her pregnancy dancing in the show, she gave birth to Don.

Four years laters, after more shows and a brief stint doing television together in Los Angeles, she and Verheeck divorced, and she moved home.

“Me being a city kid, I was born and raised in northern Jersey and I was only 18 miles from New York city, and me and my buddies any chance we got we hopped the train and went to the city.

“She was from a small town and … she liked to dance, she liked to perform … I don’t think she was actually comfortable in a city outside of work,” Verheeck said.

Sandy preferred to hang out with just a few close friends. Verheeck enjoyed the parties Sandy would decline or go.

“She would leave me at the casino, ‘Ok, see you later,’ and she would go home,” Verheeck said. “She never lost her roots in Michigan.”

And so she came home. She tried teaching dance with a partner, which fell through, and had her brief flirtation with having a conventional job, which lasted less than a year. And that made sense, because Sandy, whether she realized it or not, was already answering her own question.

What was Sandra Brewer going to do? She was going to keep being Sandra Brewer.

Act III

And, did she ever.

A few days after Sandra Brewer’s death, four women sat on Sandra Brewer’s back porch, thankful the mosquitos weren’t too bad and enjoying the shade from the towering oaks in Sandy’s backyard, the kind she had missed so dearly during her time in New York.

One was Jean Wilson, Sandy’s friend of 25 years. Another was Fran Brewer—no relation to Sandy, though they ended up like sisters. Evie Zilinksiand and Sue Mackenzie were also there. They had met Sandy through the theater, once only knowing her by her work and reputation, but who had become her partners and close friends over the years producing shows. They were among several people coming and going in the house—which was not uncommon, because Sandy’s house was an open house—people who were offering condolences, sharing memories, cooking lunch for whoever was around, gardening, and making preparations for the memorial service they would hold there Saturday that would host—who could know how many people?

But these four were different. They were the ones who were allowed to see Sandra Brewer cry.

In the early ’80s, Evie Zilinski, needed a choreographer for a show she was directing for Clio Cast & Crew, and one day she finally got the guts to call Sandy Brewer.

It was intimidating because Sandy was, well, Sandy. Sandy had choreographed some dinner theater shows that Evie had acted in, but they had yet to work side-by-side, as director and choreographer.

So she called, and asked, and Sandy said, “Of course I would!”

Remembering her reaction, Zilinski looked at the sky and mouthed, “Oh my God.”

“She was very professional, she knew what she was doing,” Zilinski said.

“She was from New York!” Mackenzie said.

“She was a star!” Fran Brewer said.

“I mean, she was a teacher,” Zilinski said. “She put things together so well. It all made sense. I mean, she understood music.”

And so they began working together, starting a decades-long friendship and partnership.

Sandy partnered with Clio Cast & Crew, and started holding shows at the Clio Amphitheater—shows that were perfect for an outdoor stage, like “Oklahoma!” “Grease,” and many others.

Her first Amphitheater show was “The Wizard of Oz,” which served as an appropriate introduction to the public on what they could expect from Sandra Brewer. For the final scene of the show, they had a hot air balloon rise unsuspectingly behind the crowd and then descend over them to pick up the wizard on stage.

The shows were also a way for her to spend time with her son, whom she once—proudly—heard rehearsing lines in the bathroom when he was about 6.

He, too, would one day go to New York and work on Broadway and tour nationally as an actor and singer.

Now home, he remembers the Clio shows as being some of the best he performed in, and the audiences noticed too, often telling them after shows that what they’d done was as good as anything they’d seen on Broadway.

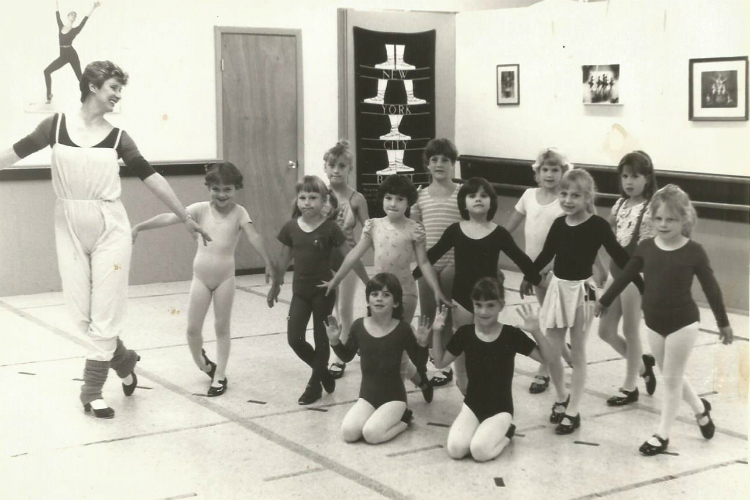

The shows were her passion. She had gone to Broadway to dance and she brought Broadway back with her, but she also needed a steady income, and so she opened—or perhaps reopened—her dance studio, Sandra Brewer’s Dance Connection, which she ran in Davison for more than 30 years.

It was a job, but it, too, was a passion. Sandy put as much work into teaching her classes and organizing her recitals as she did in any of her show. There was only one way to do things: The best way. Kamikaze.

Don Brewer, her son, said that while people knew she taught dance every day, she was working from 8 a.m. until 9 p.m. every day. Set designs had to be perfect, as did costumes—and everything else. If the costumes weren’t perfect, then Sandy would sew them.

“She wasn’t a complainer. I think she liked the work. She liked the hard work,” he said.

And she was a good friend—intensely loyal and sometimes stingingly honest. She helped friends with divorces, painted their houses, and when she had to stay at Fran Brewer’s house during a power outage, Sandy figured she would finish her friend’s under-construction Florida room while she was there, down to choosing and laying the carpet herself.

“You guys were doing a show—I think it was a recital—and she called me and she said, ‘Um. How good a friend are you,” Zilinski, said, drawing laughter from the table. “I said, ‘Well, what do you need?’ She said, ‘I need you to stop and buy me some condoms.’ ‘What?’ She said, ‘The microphones are sweating and they’re not working so we need to put them in condoms.’ So I got them.”

Later, when Clio Cast & Crew built their own indoor theater, she was able to produce, with Evie and Sue, some of her favorite shows that demanded a more intimate theater: “Cabaret” and “Chicago” being her favorites. They had the space and, after doing shows and training dancers and singer for decades in her school, she’d recruited and groomed the required talent.

And when she wasn’t teaching classes, or sewing costumes, or critiquing sets, she was involved in the community. For several years she helped organize Christmas events at the Whiting Auditorium. She would help build parade floats, and send her dancers—including her son—to places like a nearby potato festival, to participate.

Broadway, potato festival—it didn’t matter. One thing Don Brewer, her son, said he learned from her was that performing was important. It wasn’t a selfish or artistic indulgence. People deserved to be entertained, and entertainers deserved a chance to give their best performance.

“I always felt privileged because Sandy knew all of these people who we were familiar with their names. Like Bernadette Peters is the one who gave her her baby shower for Don. She’d sit down and watch TV and say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s so-and-so and that’s so-and-so, and I used to wear Cher’s dresses. Sandy had quite an illustrious career, and then she comes back—and she hangs with us,” Fran said.

Before Sandy moved home, Fran didn’t know her. She was friends with Sandy’s brother, Don, and had really only known of her or seen her on TV.

By the time they met, Fran had started dancing at another studio, but quickly became Sandy’s student, and, in time, her best friend.

“She had a knack for making even non-dancers look good. … I’d always wanted to dance. You know, even as a kid I’d watch those Drew Taylor dancers, you know, and I just wanted to dance. I just didn’t have the opportunity. And so even though I didn’t know Sandy, she was kind of like an idol to me, like, ‘God, Donnie’s sister dances, she dances on Broadway!’” she said.

Most dancers aren’t destined for Broadway, but for almost 40 years, if you lived in Genesee County, there was a woman who could make you feel like you were, look like you were, and who could push you hard enough to make you—and the people standing, cheering, holding your roses—believe it.

That was what Sandra Brewer did.

“She was,” Fran said, “magical like that.”